As I said back in 2010 "The official website’s description “powerful harrowing and ultimately inspirational story” is absolutely right." I also said "Excellent work by the filmmaker Stanley Nelson and makes me want to check out his other work." And that's what I did! I watched his film Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple (2006) and another excellent work!

When his next film came to the Maryland Film Festival 2014’s Freedom Summer I KNEW I had to see it and meet the man.The below picture is right after I saw Freedom Summer.

Freedom Summer was another excellent film and of course last year when his latest film was coming to the festival The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015) (Poster below)

I actually got a chance to hang out with Mr. Nelson last year, but that’s a story for later. I urge you to check out the works of this “Master Documentarian”.

Here are some of the titles from his filmography (hyperlinks lead to more of what I said about the films here on the blog)

Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind (2000)

The Murder of Emmett Till (2003)

Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple (2006)

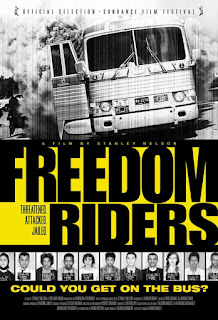

Freedom Riders (2010)

Freedom Summer (2014)

The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015)

What’s Mr. Nelson’s next films? Let him tell you via the tweets below

My next film is a 2 hr doc on the history of #HBCUs. A first ever. Follow the production at @HBCUrising. #BlackPanthersPBS— Stanley Nelson (@StanleyNelson1) February 17, 2016

It goes without saying that I’m looking forward to BOTH films!.@DrRPBenjamin Thank you! My next film after a doc on #HBCUs will look at economics of Trans Atlantic Slave Trade, btw.— Stanley Nelson (@StanleyNelson1) February 26, 2016

APRIL 2016

Emmy-winning nonfiction filmmaker Stanley Nelson will be honored at the upcoming 75th Annual Peabody Awards.

The George Foster Peabody Awards (or simply Peabody Awards) program, recognizes distinguished and meritorious public service by American radio and television stations, networks, online media, producing organizations, and individuals.

A prolific documentary filmmaker, a seeker of truth and justice, Stanley Nelson Jr. has examined the history and experience of African-Americans in a powerful, revelatory body of work that includes three Peabody winners–The Murder of Emmet Till, Freedom Summer and Freedom Riders —and ranges from Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple to Sweet Honey in the Rock: Raise Your Voice. A MacArthur Genius Fellow, Nelson is also co-founder of Firelight Media, a nonprofit organization dedicated to developing young documentary filmmakers who advance underrepresented stories.

Read more about Mr. Nelson in a 2011 New York Times article below.

___________________________________________________

An Explorer of Black History’s Uncharted Terrain

|

| Stanley Nelson |

May 3, 2011

FOR some people, filmmaking is a lifelong dream. For Stanley Nelson, it began as more of a situational thing, a response to time and place. The time was the late 1960s and early ’70s, the place to be avoided was Vietnam, the refuge was film school at the City University of New York. “It was kind of my motive to stay in school no matter what, you know what I’m saying?”

In some ways Mr. Nelson, whose graying hair is the only thing that betrays his 59 years, has been in school ever since. An accomplished director and producer of documentaries, primarily for television — his latest film,“Freedom Riders,” makes its debut on Monday night as part of the PBS series “American Experience” — he has spent his career exploring the byways of black history and culture, and passing along the stories he finds.

“I feel like I’m trying to tell African-American audiences something they haven’t heard,” he said, “because I feel like if I tell African-American audiences something new about their history, then it’s definitely going to be new for white folks too.

“In some ways,” he continued, “I’m trying not to be that guy in ‘Tarzan’ who interprets the drums for Tarzan. I don’t want to be that person.”

“Freedom Riders” is Mr. Nelson’s first film to deal directly with the civil rights movement, and he has stayed away from the “great men” of black history: Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. His subjects, in television terms, have been more everyday or more offbeat, but no less important for that: African-American newspapers, professors and vacation resorts; the black nationalist Marcus Garvey and the murder victim Emmett Till; the suicides at Jonestown; and the music of Sweet Honey in the Rock.

The breadth and seriousness of his work documenting black life in America, assembled with little fanfare and sometimes less money, place him in a select group of filmmakers that would include his mentor, William Greaves, as well as more famous names like Gordon Parks and Spike Lee. But speaking at the temporary offices of his production company, Firelight Media, on 131st Street in Harlem recently, Mr. Nelson was more the weary traveler than the auteur. He had just returned from trips to China, Houston, St. Louis and Chicago, promoting his new film, about the 1961 Freedom Rides across the South and the violent reaction they inspired.

Taking a break from his producing chores on a Firelight film about Jesse Owens, Mr. Nelson recalled the reactions to “Freedom Riders” in China.

“It was crazy,” he said, settling into a chair and commencing an off-and-on struggle to stay awake. “Some of the questions were the same as here, and some were really very, very different. One that kind of stood out was, one guy asked, ‘Why was there segregation in the U.S.?’ Which was such a beautiful question. You know, it’s so beautiful.”

Mr. Nelson’s word choices sometimes hark back to the days of peace and love, when he was an aspiring director with no interest in nonfiction (“What I knew about documentary films were those terrible documentaries that I saw in school”) and a disdain for the blaxploitation movies that constituted the movie industry’s depiction of African-Americans on-screen.

For his thesis, he made a “kind of crazy” short film about a dead woman. “I was very influenced by foreign films,” he said. “So she wakes up in the middle of a field and she goes to a psychiatrist who gives her some mumbo jumbo, and then she goes to a priest and he gives her some mumbo jumbo, and then she goes to a drug dealer and he gives her some mumbo jumbo. And then she kind of wakes up, and she’s been hit by a car.”

Out in the world, he first apprenticed with Mr. Greaves, a prolific documentary and television director and producer best known for the experimental film “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm,” and then worked for five years for the communications branch of the United Methodist Church, where, he said, he learned how to make films with a message that were still entertaining.

While there he began work on his first feature film, “Two Dollars and a Dream,” about the pioneering black businesswoman Madame C. J. Walker. The church allowed him to use its facilities for his own work one day a week. The idea came from closer to home.

“Well, my grandfather was her business partner,” Mr. Nelson said. “So the story had been circulating around my family for a long time. What’s embarrassing is that it took me so long to think of it as a film.”

It also took him a long time to make it: seven years, much of it spent raising money. The film was finally released in 1989. While conducting research on Walker, he stumbled on the subject for his next movie, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords.”

“Here were these papers that were owned and operated by black people,” he said. “And the writers were black, and the editors were black, and the photographers were black, and the cartoonists were black. I mean, somebody was making a living as a black cartoonist in 1920 — well, how about that? That’s incredible.”

Mr. Nelson’s second film took as long to make as his first, and he suspects that has had something to do with his determination to avoid familiar topics. “It took me seven years to make Madame C. J. Walker, it took me seven years to make ‘The Black Press,’ ” he said. “So going into a film, it has to be something that is really important to me. You know, because I might be seven, eight years down the line, still working on it.”

Research for “The Black Press” led Mr. Nelson to Garvey (who published the influential newspaper Negro World), and “Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind” initiated his relationship with “American Experience,” for which he has done five projects so far, including “The Murder of Emmett Till” and “Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple.” Despite the steady collaboration, each film has required a new pitch and a new negotiation. “PBS has been great, but it’s been one film after the other,” he said. “And there’s been no kind of relationship, in some terms. It’s like we meet in a bar by accident.”

“Freedom Riders” is the first film Mr. Nelson has written and directed that was not his own idea — PBS brought the project to him after optioning Raymond Arsenault’s 2006 book, “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” Asked if he had any qualms about the work for hire, Mr. Nelson laughed and said, “Well, I think they had raised all the money.”

“And I always kind of wanted to do a film about the civil rights movement, about one piece of the civil rights movement,” he added. “About dissecting a piece of it, because I think ‘Eyes on the Prize’ was a great, great, beautiful series, but it kind of made this whole lump thing of the movement.”

Mr. Nelson’s “American Experience” films can be found on DVD from shoppbs.org and other online retailers, but his other films are harder to track down. (“Two Dollars and a Dream” can be bought at filmakers.com, which caters to institutional customers, for $350.) Those with a Netflix subscription, however, have access to a special treat: “A Place of Our Own,” his best and most atypical film, is currently available for streaming.

That 2004 work, conceived as a straightforward documentary about black resort towns around the country, became a poetic and highly personal film about Mr. Nelson’s family summer home at Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, his parents and siblings, and a set of issues not often aired in public: the fault lines of class, generation and skin color that exist among African-Americans.

“It was more personal than I ever realized it would be, than I ever wanted it to be, than it will ever be again,” he said of “A Place of Our Own.” He had to be persuaded — “over and over and over again” — to allow the editors to put the focus on his fractured relationship with his father and to record the wistful first-person narration that sets the film’s tone.

Part of the story it tells is of Mr. Nelson’s upper-middle-class upbringing, with a dentist father and librarian mother who sent him to a progressive private school in Manhattan and whisked him off to Martha’s Vineyard every summer. Both “pieces” of his childhood, as he calls them, were cocoonlike (to put it one way) and intensely supportive (to put it another).

They did not remove “the kind of disconnect and disassociation that I think all black people have,” he said, but they did give him “some feeling of comfort in the world.” And they informed the kind of filmmaker he would become.

“I’m just trying to make the best film that I possibly can,” he said. “I’m not carrying a lot of baggage. I’m not thinking about this or that. I’m not bitter. And that’s kind of how I see myself.”

In addition to producing the Jesse Owens film, Mr. Nelson is negotiating with PBS and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to do a connected series of films on topics including the slave trade, historically black colleges and the Black Panther party. He would like to direct a film about the Panthers, a favorite subject, himself. But there’s another topic — another subject of study — about which he seems to be even more excited.

“I’ve always wanted to do a film about James Brown,” he said. “Because I love James Brown, and I think it’s kind of this great story, and great music. I do think there’s something about that music. You know, especially for black people. You say James Brown, people start to smile. Why? Why is it that people start to smile? I’m not there yet.”

In some ways Mr. Nelson, whose graying hair is the only thing that betrays his 59 years, has been in school ever since. An accomplished director and producer of documentaries, primarily for television — his latest film,“Freedom Riders,” makes its debut on Monday night as part of the PBS series “American Experience” — he has spent his career exploring the byways of black history and culture, and passing along the stories he finds.

“I feel like I’m trying to tell African-American audiences something they haven’t heard,” he said, “because I feel like if I tell African-American audiences something new about their history, then it’s definitely going to be new for white folks too.

“In some ways,” he continued, “I’m trying not to be that guy in ‘Tarzan’ who interprets the drums for Tarzan. I don’t want to be that person.”

“Freedom Riders” is Mr. Nelson’s first film to deal directly with the civil rights movement, and he has stayed away from the “great men” of black history: Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. His subjects, in television terms, have been more everyday or more offbeat, but no less important for that: African-American newspapers, professors and vacation resorts; the black nationalist Marcus Garvey and the murder victim Emmett Till; the suicides at Jonestown; and the music of Sweet Honey in the Rock.

The breadth and seriousness of his work documenting black life in America, assembled with little fanfare and sometimes less money, place him in a select group of filmmakers that would include his mentor, William Greaves, as well as more famous names like Gordon Parks and Spike Lee. But speaking at the temporary offices of his production company, Firelight Media, on 131st Street in Harlem recently, Mr. Nelson was more the weary traveler than the auteur. He had just returned from trips to China, Houston, St. Louis and Chicago, promoting his new film, about the 1961 Freedom Rides across the South and the violent reaction they inspired.

Taking a break from his producing chores on a Firelight film about Jesse Owens, Mr. Nelson recalled the reactions to “Freedom Riders” in China.

“It was crazy,” he said, settling into a chair and commencing an off-and-on struggle to stay awake. “Some of the questions were the same as here, and some were really very, very different. One that kind of stood out was, one guy asked, ‘Why was there segregation in the U.S.?’ Which was such a beautiful question. You know, it’s so beautiful.”

Mr. Nelson’s word choices sometimes hark back to the days of peace and love, when he was an aspiring director with no interest in nonfiction (“What I knew about documentary films were those terrible documentaries that I saw in school”) and a disdain for the blaxploitation movies that constituted the movie industry’s depiction of African-Americans on-screen.

For his thesis, he made a “kind of crazy” short film about a dead woman. “I was very influenced by foreign films,” he said. “So she wakes up in the middle of a field and she goes to a psychiatrist who gives her some mumbo jumbo, and then she goes to a priest and he gives her some mumbo jumbo, and then she goes to a drug dealer and he gives her some mumbo jumbo. And then she kind of wakes up, and she’s been hit by a car.”

Out in the world, he first apprenticed with Mr. Greaves, a prolific documentary and television director and producer best known for the experimental film “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm,” and then worked for five years for the communications branch of the United Methodist Church, where, he said, he learned how to make films with a message that were still entertaining.

While there he began work on his first feature film, “Two Dollars and a Dream,” about the pioneering black businesswoman Madame C. J. Walker. The church allowed him to use its facilities for his own work one day a week. The idea came from closer to home.

“Well, my grandfather was her business partner,” Mr. Nelson said. “So the story had been circulating around my family for a long time. What’s embarrassing is that it took me so long to think of it as a film.”

It also took him a long time to make it: seven years, much of it spent raising money. The film was finally released in 1989. While conducting research on Walker, he stumbled on the subject for his next movie, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords.”

“Here were these papers that were owned and operated by black people,” he said. “And the writers were black, and the editors were black, and the photographers were black, and the cartoonists were black. I mean, somebody was making a living as a black cartoonist in 1920 — well, how about that? That’s incredible.”

Mr. Nelson’s second film took as long to make as his first, and he suspects that has had something to do with his determination to avoid familiar topics. “It took me seven years to make Madame C. J. Walker, it took me seven years to make ‘The Black Press,’ ” he said. “So going into a film, it has to be something that is really important to me. You know, because I might be seven, eight years down the line, still working on it.”

Research for “The Black Press” led Mr. Nelson to Garvey (who published the influential newspaper Negro World), and “Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind” initiated his relationship with “American Experience,” for which he has done five projects so far, including “The Murder of Emmett Till” and “Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple.” Despite the steady collaboration, each film has required a new pitch and a new negotiation. “PBS has been great, but it’s been one film after the other,” he said. “And there’s been no kind of relationship, in some terms. It’s like we meet in a bar by accident.”

“Freedom Riders” is the first film Mr. Nelson has written and directed that was not his own idea — PBS brought the project to him after optioning Raymond Arsenault’s 2006 book, “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” Asked if he had any qualms about the work for hire, Mr. Nelson laughed and said, “Well, I think they had raised all the money.”

“And I always kind of wanted to do a film about the civil rights movement, about one piece of the civil rights movement,” he added. “About dissecting a piece of it, because I think ‘Eyes on the Prize’ was a great, great, beautiful series, but it kind of made this whole lump thing of the movement.”

Mr. Nelson’s “American Experience” films can be found on DVD from shoppbs.org and other online retailers, but his other films are harder to track down. (“Two Dollars and a Dream” can be bought at filmakers.com, which caters to institutional customers, for $350.) Those with a Netflix subscription, however, have access to a special treat: “A Place of Our Own,” his best and most atypical film, is currently available for streaming.

That 2004 work, conceived as a straightforward documentary about black resort towns around the country, became a poetic and highly personal film about Mr. Nelson’s family summer home at Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, his parents and siblings, and a set of issues not often aired in public: the fault lines of class, generation and skin color that exist among African-Americans.

“It was more personal than I ever realized it would be, than I ever wanted it to be, than it will ever be again,” he said of “A Place of Our Own.” He had to be persuaded — “over and over and over again” — to allow the editors to put the focus on his fractured relationship with his father and to record the wistful first-person narration that sets the film’s tone.

Part of the story it tells is of Mr. Nelson’s upper-middle-class upbringing, with a dentist father and librarian mother who sent him to a progressive private school in Manhattan and whisked him off to Martha’s Vineyard every summer. Both “pieces” of his childhood, as he calls them, were cocoonlike (to put it one way) and intensely supportive (to put it another).

They did not remove “the kind of disconnect and disassociation that I think all black people have,” he said, but they did give him “some feeling of comfort in the world.” And they informed the kind of filmmaker he would become.

“I’m just trying to make the best film that I possibly can,” he said. “I’m not carrying a lot of baggage. I’m not thinking about this or that. I’m not bitter. And that’s kind of how I see myself.”

In addition to producing the Jesse Owens film, Mr. Nelson is negotiating with PBS and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to do a connected series of films on topics including the slave trade, historically black colleges and the Black Panther party. He would like to direct a film about the Panthers, a favorite subject, himself. But there’s another topic — another subject of study — about which he seems to be even more excited.

“I’ve always wanted to do a film about James Brown,” he said. “Because I love James Brown, and I think it’s kind of this great story, and great music. I do think there’s something about that music. You know, especially for black people. You say James Brown, people start to smile. Why? Why is it that people start to smile? I’m not there yet.”

No comments:

Post a Comment